For as long as many of us can remember, Silicon Valley has sought to conquer the world. It believes technology is the solution to the world’s problems, and in the words of the famous venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, “software will eat the world.” Silicon Valley has never been short of candidates advancing its claim, but even in the world of superstars and adrenalin-soaked egos, Elon Musk is exceptional and might be the best placed to take the geeks closer to their goal of world domination. Agree Layara reports.

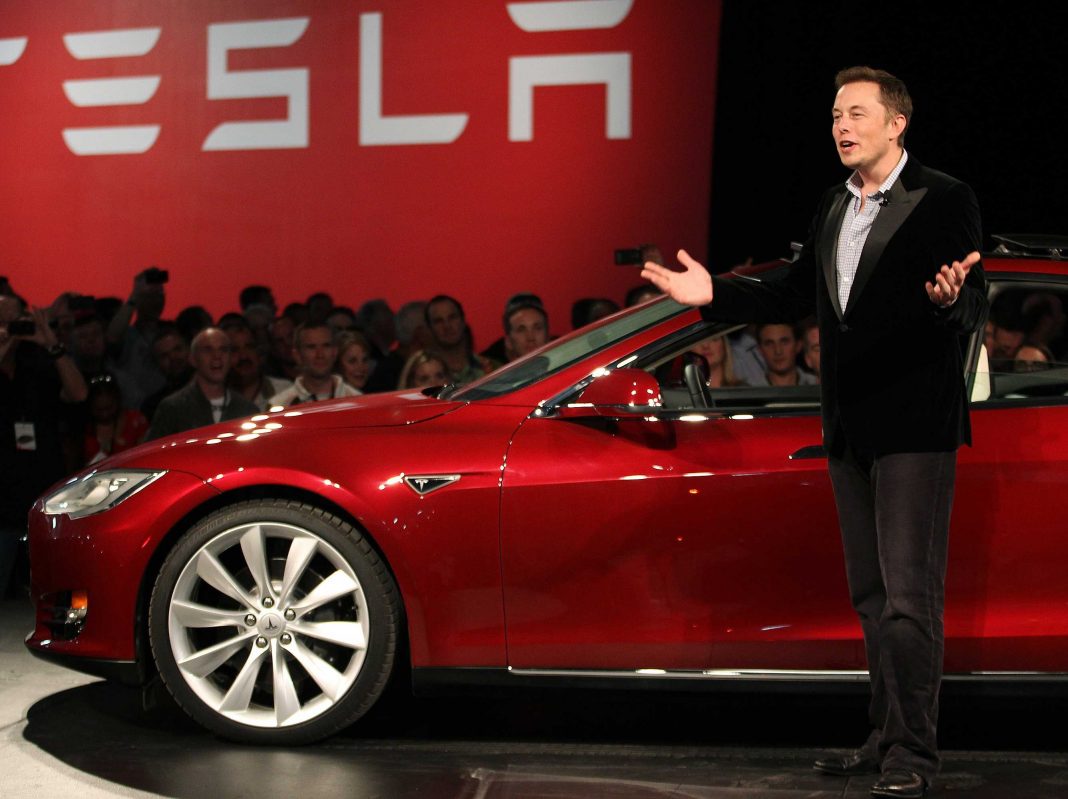

Like many, or maybe most, emerging from Silicon Valley, Musk is loved and hated, perhaps in equal measure. He is often hailed as a climate change hero for his solar energy initiatives and the Tesla electric car, to many a thing of beauty. But he is just as often seen as a despot – he fired nearly everybody that mattered at Tesla Motors when he took control in a crisis nine years ago – and delusional for his grand constellation of projects ranging from space (SpaceX) to earth (hyperloop), energy (SolarCity) and mind (Neuralink). But what critics really hate, perhaps without recognising it, is his style, not substance. Musk has suffered several setbacks, notably in Tesla’s early years, but also with SpaceX and SolarCity, and missed deadlines, but most of his projects are rooted in what he calls the “first principles” of physics, Musk’s primary field of academic study, and continue to make measured progress.

It’s tempting to believe 2017 might be Musk’s year. It has started out well. In just a few weeks, Tesla stock is up a whopping 40%, as the company ramps up production plans for the Model 3 – the $35,000 car that challenges the likes of BMW on specifications and price. The rise also helped the company overtake Ford Motor Co. and General Motors in market capitalisation. This is remarkable in the quest to overthrow Detroit because Tesla’s annual revenue in 2016 was less than 5% of GM’s. Sceptics still believe Tesla’s ambitious numbers won’t add up, but Musk is marching on with plans to produce 500,000 cars annually by 2018.

Then his other company, SpaceX, finally succeeded in sending into space a used rocket. It is the first time anybody has done that. To understand its significance, consider that nations launch less than 150 rockets into space every year, notably because of the cost. It takes several millions of dollars for each rocket launch, primarily because the rockets cannot be reused. With the Falcon 9, Musk has fundamentally altered that cost equation, perhaps paving the way for large-scale exploration of space, and eventual colonisation of Mars. Musk, in fact, has expressed a desire to die on Mars, “just not on impact.”

Then his other company, SpaceX, finally succeeded in sending into space a used rocket. It is the first time anybody has done that. To understand its significance, consider that nations launch less than 150 rockets into space every year, notably because of the cost. It takes several millions of dollars for each rocket launch, primarily because the rockets cannot be reused. With the Falcon 9, Musk has fundamentally altered that cost equation, perhaps paving the way for large-scale exploration of space, and eventual colonisation of Mars. Musk, in fact, has expressed a desire to die on Mars, “just not on impact.”

Also this year, Musk threw his weight behind Neuralink, according to The Wall Street Journal. Neuralink bids to make devices that can be implanted in the human brain, adding a layer of digital intelligence. Not much else is known, but media, parsing Musk’s comments on the subject, believe Neuralink will initially build devices that help relieve conditions like Parkinson’s. The human brain, of course, is extremely complex and probably the last frontier for technology. Musk’s fascination with neural lace – a fictional term coined by the science fiction writer Iain Banks – could also stem from his dread of artificial intelligence, which he has termed the “demon.” Neuralink might be his way of raising the capabilities of the human brain and preparing man for success in an emerging, unknown, world.

How did Musk learn to dream?

Born in South Africa, Musk traced his roots to Britain (paternal grandmother), Canada (mother) and the United States (maternal grandfather). He attended school in Pretoria,

and lived mostly with his father after his parents divorced when he was just eight. In this pre-Internet era, and period of solitude – Musk had few friends and was often bullied in school – he is believed to have fallen in love with the printed word.

Musk was once asked how he learned to build rockets. He said: “I read books.” It is reasonable to assume the answer would have been no different had somebody asked him how he dreamed up his projects for adulthood. Musk delved into two broad categories of books – science and science fiction, and biographies. So, he took in Isaac Asimov, Douglas Adams, John D. Clark, Iain M. Banks and James Barrat (“Our Final Invention” on AI). In biographies, he read Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein and Howard Hughes. The two sets of tomes shaped him differently. Reading the first broadened his understanding of the world and his horizons, and reading the other made him place himself at the centre of things, perhaps setting the agenda for his career. “The heroes of the books I read, ‘The Lord of the Rings’ and the ‘Foundation’ series, always felt a duty to save the world,” he told The New Yorker.

Musk is often, and favourably, compared to Steve Jobs, a maverick genius who cofounded Apple and in a second coming created ground-breaking products as the iMac, iPod, iPhone and iPad. But the two have far less in common than you might think. Where Jobs conquered the stage, Musk can only conquer Twitter, but where Jobs took your breath away with beautiful computing devices, the South African-born takes your breath away with the range of his vision for technology and humanity.

If he succeeds with his projects – as seems likely, except perhaps the hyperloop – Musk might, among other things, help man breathe better, think better with the help of computers, and conquer new worlds in outer space. It might sound like science fiction, but all are in the realm of the possible, and perhaps closer than we think.

Now, if you still want to compare Jobs with Musk, you could seriously be in danger of making the Apple boss look mediocre, rather than the genius he was. Musk is Jobs on steroids. At 45, he’s got a way to go, too.