As tensions between Washington and Beijing intensify over control of rare earth elements, a less-discussed casualty has begun to emerge: Europe. While the United States moves swiftly to secure its supply chains and China tightens its grip on strategic exports, Europe finds itself trapped in a widening gap — heavily exposed, slow to adapt, and structurally dependent on both sides. The rare earth conflict, once a niche issue confined to technocrats and defence planners, has become a geopolitical stress test that Europe is failing.

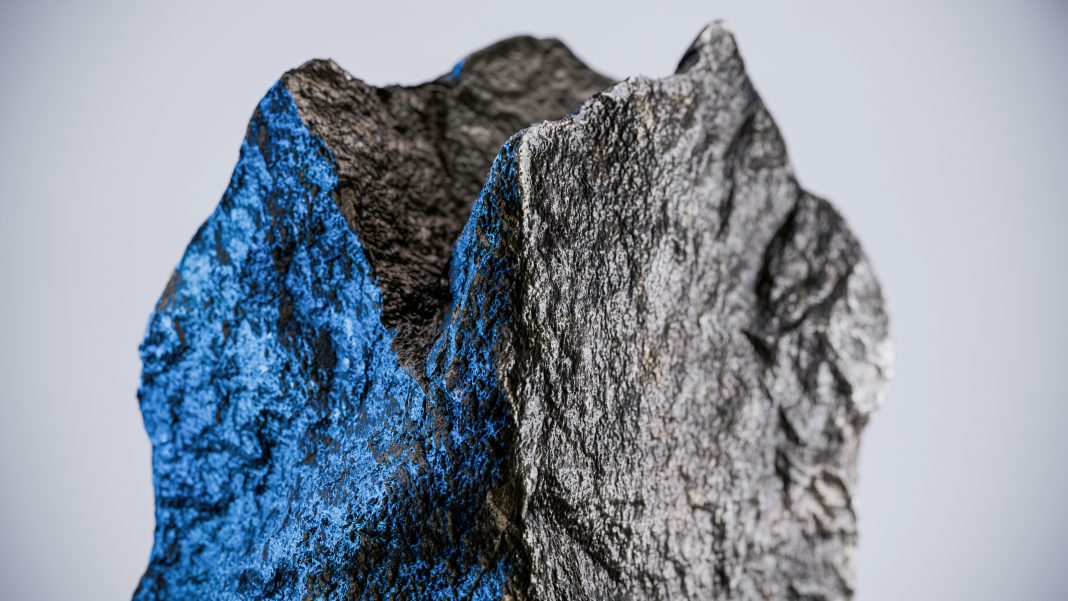

Rare earth elements, a group of seventeen obscure but indispensable materials, underpin everything from smartphones and electric vehicle motors to wind turbines and missile guidance systems. Although the raw ores can be found across the globe, China dominates the refining and separation process, controlling more than 90 per cent of global capacity. Over the past year, Beijing has begun wielding that dominance with new confidence. It first imposed export restrictions on key metals and magnet-making equipment in the spring, and in October expanded those measures further to include most of the 17 rare earths. The move was presented as an environmental policy, but few in European capitals doubt the political intent. It is the latest turn in an economic confrontation in which raw materials have become weapons.

Washington’s response has been characteristically muscular. The Biden administration has channelled billions into domestic processing, signed critical-mineral pacts with allied countries, and framed the issue as part of a wider strategy of “de-risking” from Chinese dependence. Europe, however, has no comparable plan. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, passed earlier this year, set out bold targets for local sourcing and refining capacity, but its implementation has lagged behind both ambition and necessity. Europe’s heavy industry — from automotive to clean energy — is now staring at a supply chain crunch that could ripple through production lines this winter.

Europe’s vulnerability stems from the structure of its economy. For decades, the continent has specialised in high-value manufacturing and design, leaving the extraction and processing of key inputs to external suppliers. That model has worked well in a globalised system where trade flowed freely. In a world defined by supply weaponisation, it has become a liability. The European auto sector, pivoting at breakneck speed towards electric mobility, depends on permanent magnets that require rare earths such as neodymium and dysprosium. Without them, production halts. German and Italian manufacturers are already reporting shortages and price spikes. Defence companies face similar exposure, with guidance systems, radar, and sensor technologies reliant on the same critical materials.

Yet even when Europe recognises its vulnerability, it struggles to act. The continent’s environmental and planning regulations — among the strictest in the world — have made it nearly impossible to build large-scale mining or refining operations. Projects in Sweden and Finland remain mired in local opposition, bureaucratic delay, and litigation. The EU’s rhetoric of strategic autonomy collides with the political reality of communities unwilling to accept new industrial activity on their doorstep. Where the US can invoke national security to fast-track projects, Europe’s consensus-driven system fragments responsibility across national, regional, and EU levels. The result is paralysis.

The problem is not only regulatory. It is financial and strategic. The US has paired its industrial revival with massive public subsidies and clear strategic direction. China, for its part, treats rare earths as an instrument of state power. Europe, by contrast, has relied on market mechanisms that assume rational behaviour by trading partners. That assumption no longer holds. The EU’s investment in rare-earth processing and magnet production remains negligible, and the bloc has been slow to court alternative suppliers in Africa, Australia or Latin America. Even where trade agreements exist, Europe has been cautious about linking them to raw material security. Meanwhile, Washington is locking in long-term offtake deals with the very countries Europe needs to engage.

The consequences are already visible. According to data from customs authorities, Chinese exports of rare earths dropped by nearly one-third in September, well before the full impact of new restrictions takes effect. European companies have begun stockpiling magnets and components, but inventories are limited. Smaller manufacturers, particularly in the electronics and renewable sectors, cannot afford to build reserves. The result is mounting anxiety across industries critical to Europe’s green transition and defence readiness. In Italy, an auto industry lobby recently warned that rare-earth curbs could derail the continent’s electric vehicle rollout. In Germany, business associations are pressing Berlin to secure bilateral deals with resource-rich partners.

Diplomatically, the EU has tried to keep pace with Washington, calling for a united front and deeper coordination on critical minerals. Yet even here, Europe’s voice is hesitant. Some member states, anxious about economic retaliation, prefer to avoid direct confrontation with Beijing. Others prioritise maintaining access to China’s vast consumer market. The bloc’s collective response risks being too slow and too fragmented to matter. As the US moves quickly to insulate itself from supply shocks, Europe remains exposed — and increasingly dependent on the goodwill of others.

This imbalance reflects a deeper structural challenge. Europe’s industrial and technological model was built in a period of liberal globalisation, when efficiency mattered more than resilience. The rare-earth crisis reveals the fragility of that approach. The EU’s ambition to lead in electric vehicles, renewable energy, and digital technologies all depends on inputs it does not control. In an age of economic nationalism and supply-chain militarisation, that is a strategic contradiction. Without upstream control, Europe’s downstream industries risk becoming collateral damage in the new resource geopolitics.

Some policy thinkers in Brussels argue that Europe can still recover ground. They point to the continent’s strengths in recycling, materials science, and advanced engineering. By scaling up recycling of end-of-life magnets, investing in substitution technologies, and co-financing new processing plants, Europe could reduce its dependence over time. The Commission has also floated the idea of a European rare-earth stockpile, modelled on strategic petroleum reserves. But such measures require coordination, capital, and political urgency — qualities that Europe has often struggled to muster.

For now, the momentum lies elsewhere. The US is building new processing facilities in Texas and California, Australia is expanding its mining output, and China continues to refine its grip on global supply. Europe remains largely an observer, watching as the two great powers redraw the map of industrial sovereignty. The irony is that the continent that prides itself on its environmental and technological leadership may find its clean-energy revolution throttled by shortages of the very materials needed to power it.

The rare earth wars are no longer a distant skirmish in trade policy. They have become a defining feature of 21st-century geopolitics — a contest over who controls the essential ingredients of modern life. Europe, so far, has not chosen to fight that battle with the urgency it demands. Unless that changes, the continent risks sliding from industrial power to strategic bystander, caught between an assertive China and an increasingly self-reliant America. In the new age of resource competition, it is not ideology or intent that decides winners and losers, but the hard arithmetic of supply, demand, and control. By that measure, Europe is losing.